This article will discuss the stigma that surrounds the diagnosis of schizophrenia. I will argue that much of the stigma about schizophrenia is directly attributable to the way that the psychiatric profession framed it more than a century ago, and how the profession has responded to it since that time.

I will also argue that much of the pessimism that attends the diagnosis of schizophrenia is unfounded.

I’ll propose four things that clinicians can do (and should do often) that can help undo the unfounded stigma about schizophrenia.

Why is it important to reverse the stigma around schizophrenia?

It’s obvious that stigma is bad. But let’s take a look at some of the data that shows just how damaging schizophrenia stigma can be. People facing higher levels of stigma are more likely to experience:

Furthermore, the stigma around schizophrenia has negative consequences on patient outcomes in medical settings (Chochinov et al., 2009, Lord et al., 2010). People with schizophrenia often receive less and lower quality health care compared to people without mental illness. Compared to other patient groups, people with schizophrenia are also less likely to be referred for routine preventative care, such as mammography, osteoporosis screening, vaccinations, weight loss programs, and blood pressure and cholesterol monitoring.

Additionally, people with schizophrenia are more likely to be disadvantaged by “diagnostic overshadowing,” which is when a patient with a prior psychiatric diagnosis receives inadequate medical treatment for physical symptoms because a doctor ascribes the symptoms to their psychiatric diagnosis rather than considering them a sign of another medical illness. For example, a person reports their concerns about shortness of breath. Since this person was previously diagnosed with schizophrenia, their doctor concludes that the shortness of breath is caused by anxiety, a comorbidity of schizophrenia, without exploring other medical possibilities.

These negative effects of stigma can result in a vicious circle where we might witness a lot of people with this illness who do poorly and therefore reassert our assumptions that schizophrenia is a dire diagnosis from which people do not improve.

However, it is now clear that a lot of the assumptions we previously made about the illness itself can actually be attributed to the structures we’ve built around it.

“Many would now contend that much of the poor outcome in psychosis is an artifact of late detection, crude and reactive pharmacotherapy, sparse psychosocial care, and social neglect.”

McGorry et al., 2013

Why are stigma and pessimism so prevalent among clinicians?

Stigmatizing attitudes around schizophrenia are just as common among healthcare professionals as the general public and may be even more prevalent and severe in mental health clinicians than in the general population (Üçok et al., 2004, Thornicroft et al., 2009, Ihalainen-Tamlander et al., 2016).

Treatment in health media

One potential reason for the prevalence of stigmatizing attitudes may stem from how schizophrenia is (or is not) covered in health media. In general, schizophrenia is not discussed, even though more people in the U.S. are living with schizophrenia than Type 1 diabetes, or lupus, or multiple sclerosis. The number of Americans living with schizophrenia is about twice as large as the number in active military service. And 1 in 11 Americans will report a psychotic experience over their lifetime—making schizophrenia the most common problem that nobody talks about.

When schizophrenia is mentioned in health media, it is often mentioned in conjunction with reports of violence, homelessness, or other serious problems. These reports also often continue to use outdated language and reinforce the myth of split mind or multiple personality in schizophrenia. When is the last time you heard a story about someone with schizophrenia becoming a nurse, or a business owner, or a university professor, or a loving parent?

Poor use of language

The use of inaccurate and outdated language is another potential major cause for the prevalence of stigma around schizophrenia. The word “schizophrenia” is derived from Greek, meaning “splitting of the mind” but we now know that “split mind” is an inaccurate characterization of the disorder.

Furthermore, words like “psychotic” and “schizophrenic” have become pejorative adjectives and derogatory slurs in common English. Many outdated or pejorative terms were updated for other areas of psychology in the DSM-5—like manic depression and dysthymia—but the language around schizophrenia remained unchanged. We appropriately condemn the use of race-based adjectives to convey a negative sentiment. There’s no such outrage when people do with psychosis or schizophrenia.

In many hospitals and other clinical settings, phrases like “psychotic break,” “break with reality,” and “hit them with medication to put them down” are commonly used when treating schizophrenia patients. The language of breakage is appropriate only in orthopedics. It has no business being applied to people, or their brains, or their thoughts or emotions.

Low expectations ingrained in the medical profession

Lastly, the stigma around schizophrenia is likely so prevalent and severe amongst clinicians because medical school and professional training programs largely still teach that schizophrenia is a permanent, progressively declining disorder with poor outcomes.

For centuries, dogma has been that schizophrenia is incurable, so if someone achieves recovery or remission then they must have been misdiagnosed.

Until recent history, many schizophrenia treatments were ineffective and often actually worsened patient outcomes. People with schizophrenia were often placed in poor living situations that were not conducive to recovery. When medications were found effective for schizophrenia, they were often overdosed at excessive quantities under the assumption that “more is better,” but this resulted in horrible side effects and poor outcomes for patients. These factors enforced pessimism and stigma around schizophrenia and the myth that patients could not get better.

What’s the real prognosis with schizophrenia?

Studies have shown that many people with schizophrenia can and do achieve recovery and remission. And their outcomes are even better with early detection and early treatment, but stigma can often interfere with treatment. Historically, those who foster optimism and encourage recovery have been accused of providing false hope, but data shows that recovery and remission are realistic goals.

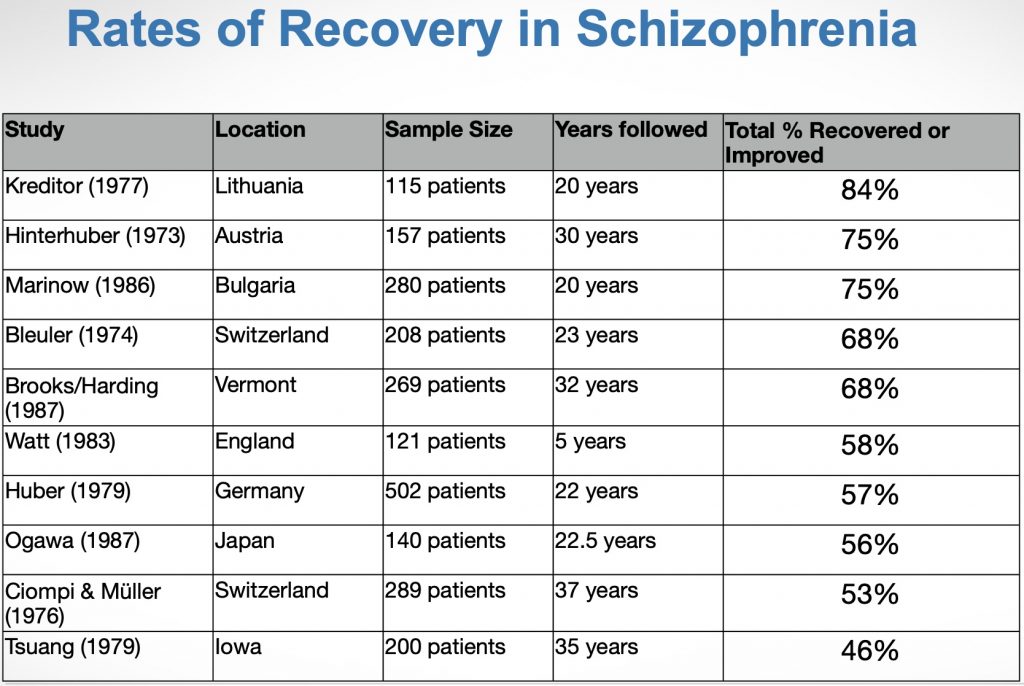

Recovery is defined as a person having the ability to return to their former position in society, be employed or do meaningful work, and maintain supportive family relationships. Long-term studies have found that anywhere from 46-84% of people with schizophrenia achieve recovery, which is on average 65% or about two-thirds of people.

- Long-term studies have found that anywhere from 46-84% of people with schizophrenia achieve recovery, which is on average 65% or about two-thirds of people.

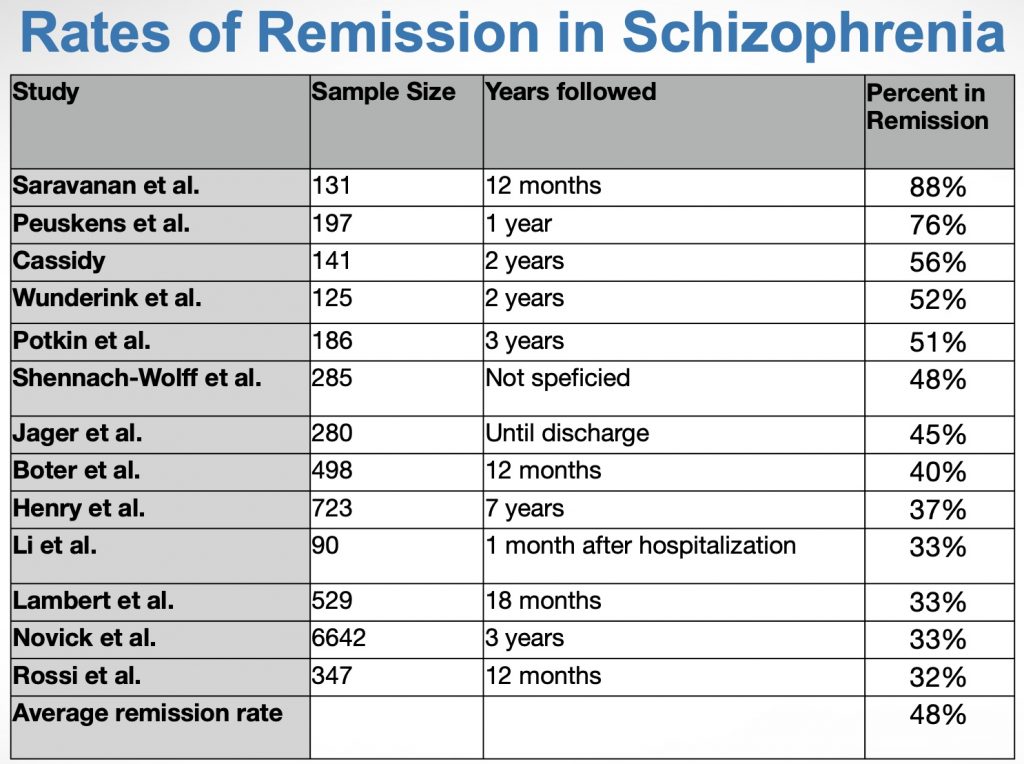

Remission is a bit more narrowly defined than recovery. Remission is defined as the absence or near absence of symptoms for at least 6 months, with no sign of active illness long-term. Long-term studies have found that anywhere from 33-80% of people with schizophrenia achieve remission, which is on average 50% or about half of people.

- Long-term studies have found that anywhere from 33-80% of people with schizophrenia achieve remission, which is on average 50% or about half of people.

With this data, there are many reasons to be hopeful about recovery and remission for people with schizophrenia.

Improving outcomes for people with schizophrenia (it’s not all about medication)

The historical view of schizophrenia is of an illness with mysterious yet powerful biological determinants. The historical view of schizophrenia gave very little serious credence to the study of environmental, social, or psychological factors as treatment tools.

However, we now know that environmental, social, or psychological factors account for about half of the risk for developing schizophrenia. These non-biological (and eminently modifiable) factors have substantial influence on the outcome of the illness.

We, as medical professionals, have the ability to make things better for people with schizophrenia if we complement effective medication with fostering and encouraging the following positive factors over the course of treatment:

- Improved attitudes towards illness and treatment

- Adherence to treatment

- Avoidance of psychotogenic substances

- A supportive family or social network

- Obtain or return to meaningful work, school, or activity

- Physical activity and improved physical health

- Realistic hope of meaningful and maximal recovery

4 ways clinicians can reverse the stigma and pessimism around schizophrenia

- Create a culture of unrelenting optimism around schizophrenia recovery in your practice

- Always set the goal for the highest possible level of recovery in your practice

- Advocate that other systems of care organize their services around the goal of full recovery

- Spend as much time talking about dreams and goals with your patients as you spend discussing symptoms or impairment

Learn more:

You can find a lecture with more information on the relationship between marijuana and depression on my YouTube channel, 15-Minute Pharmacology. The lecture was given at the January 29, 2019 meeting of the SZconsult learning community.

Disclaimers

This article summarizes the results and conclusions of articles published in the medical literature. It is for general information. It is not a substitute for medical advice, and readers are admonished not to enact or change treatments based on this article. Always seek the advice of your doctor before starting or changing treatment.

The thoughts, views, and opinions expressed in this article are my own and do not reflect or represent the policy or position of Northeast Ohio Medical University.